The major European competition among football teams, the Champions League (CL), was organized as a successor to the European Champion Clubs’ Cup – often simply referred to as the “European Cup” (EC) – in which national league winners competed in a knockout tournament from its inception in 1955. The CL initially implied a change from a knockout tournament to a hybrid combining a round robin tournament in which groups of four teams compete to determine qualifiers and a knockout tournament between the qualified teams (Scarf et al., 2009). Later, UEFA also changed the admission rules. As in the EC, the first editions of the CL included only national league champions (and the titleholder). From 1999 onwards, multiple teams from the highest ranked leagues were admitted. Since the 1999/2000 season, the runners-up from the six highest ranked leagues, assigned according to the official UEFA coefficients, also directly qualify for the group-round. Since the 2009/10 season, the third-placed teams of the three highest ranked countries also qualify directly.

Both the popular press and academic studies argue that the change from the EC to the CL has made the CL less exciting and its outcomes more predictable. However, the argument that the CL’s outcomes are more predictable seems inconsistent with ad hoc observations on the history of EC and CL winners. Several teams were able to win the EC several times in a row. In fact, in 13 out of 37 seasons, the winner of the EC was the winner of the previous season. In contrast, not a single team has been able to win the CL twice in a row. This observation seems inconsistent with the argument that the CL rules have made the major European competition less exciting and more predictable.

We borrow from the operational research literature to predict how the tournament format influences the tournament outcomes. Scarf et al. (2009) simulate CL outcomes for 11 different possible tournament formats. The simulated formats include the format of the EC and the current format of the CL. The simulation estimates show that the average ranking of the teams that qualify for the different knockout rounds in later rounds is higher for the current CL format than for the EC format. This suggests that, on average, the highly ranked teams who participate in the tournament are more likely to qualify for the round of 16 in the CL than in the EC, and vice versa for lowly ranked teams. These simulation results do not take into account the effect of UEFA’s decision to allow multiple teams from the highest ranked leagues to qualify directly for the CL (compared to only one team per league for the EC). Because of this decision, it is more likely that a specific highly ranked team from one of the highest ranked leagues qualifies year after year since they qualify even if they do not win the title in their national league but end second (or third).

However, another effect of UEFA’s decision to allow multiple teams from the highest ranked leagues to qualify directly for the CL (compared to only one team per league for the EC) and of the knockout format versus the hybrid format is that the average ranking of the qualified teams is higher, and that the quality difference between the teams is smaller at later stages in the tournament. This implies that it is more difficult for a specific highly ranked team from one of the highest ranked leagues to progress at later stages in the tournament.

In sum, the introduction of the group-round and the rule change towards direct qualification for multiple teams from the highest ranked leagues has made it more likely for a specific highly ranked team from one of the highest ranked leagues to qualify for the round of 16 in the CL than in the EC and – at the same time – less likely to qualify for later stages in the CL than in the EC. Hence, we predict that on average it is easier to predict who will qualify for the lower rounds in the CL than in the EC and harder to predict who will qualify for later stages in the CL than in the EC.

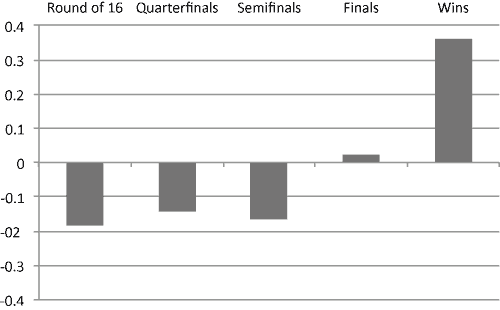

In a recent paper (Schokkaert and Swinnen, 2013), we calculate an indicator which is commonly used in the literature, “uncertainty of outcome” (UO), to provide evidence for these predictions. Figure 1 shows the difference in our UO indicator between the CL and the EC for the various knockout rounds and for winning the tournament. The figure shows that the difference in the UO indicator between the CL and the EC is negative for the round of 16, the quarterfinals and the semifinals. On the other hand, the difference in the UO indicator between the CL and the EC is positive for the finals and for winning the tournament. These empirical indicators are consistent with our hypotheses that it is easier to predict who will qualify for lower rounds in the CL than in the EC and that, at the same time, it is harder to predict who will qualify for later stages in the CL than in the EC.

Figure 1 Differences in uncertainty of outcome between the Champions League (1992-2011) and the European Cup (1955-1991)

Notes: (i) The Figure shows the difference in the teams’ average probability of qualifying for the different knockout rounds (or winning) in one season and not qualifying (or not winning) in the next season between the Champions League and the European Cup. A positive difference is associated with higher uncertainty of outcome in the Champions League and vice versa.

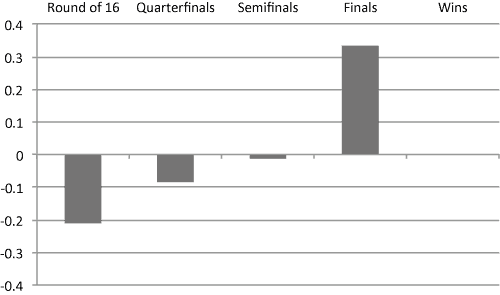

Next, we can try to see which of the rule changes under the CL was crucial in causing the effects, the change in tournament format or in admission rules. The second change (direct qualification for multiple teams from the highest ranked leagues) was implemented only in 1999 when the CL was already in place for several years. Figure 2 shows the difference in UO indicators between the CL after 1999 and before 1999. There is a strong relationship. The difference in the UO indicator is negative for the round of 16 and the quarterfinals. There is almost no difference in the semifinals and the difference in the UO indicator is positive for the finals. This suggests that it is in particular the change in the admission rules that makes it easier to predict who will qualify for lower rounds in the CL and harder to predict who will qualify for later stages in the CL.

Figure 2 Differences in uncertainty of outcome between the Champions League after 1999 (1999-2011) and before 1999 (1992-1998)

Notes: (i) The Figure shows the difference in the teams’ average probability of qualifying for the different knockout rounds (or winning) in one season and not qualifying (or not winning) in the next season between the Champions League after and before 1999. A positive difference is associated with higher uncertainty of outcome after 1999 and vice versa. (ii) No club has won the Champions League twice in a row, such that the difference in uncertainty of outcome between the Champions League after 1999 and before 1999 equals 0 for this stage.

Admittedly, whereas 37 EC editions were organized, only 20 CL editions have been organized up to now. However, our results are robust to comparing our empirical indicator over periods of equal length (see Schokkaert and Swinnen, 2013).

Right before the start of the quarterfinals of the current 2012/13 Champions League, we observe that only three out of eight teams also reached this knockout round last season (Barcelona, Bayern Munich, Real Madrid) and that the winner of the previous edition (Chelsea) even failed to qualify for the round of 16. Hence, this year’s competition seems to confirm our empirical findings that outcomes at later stages have become less predictable and thus that it is harder, not easier, to predict the winner of the CL.