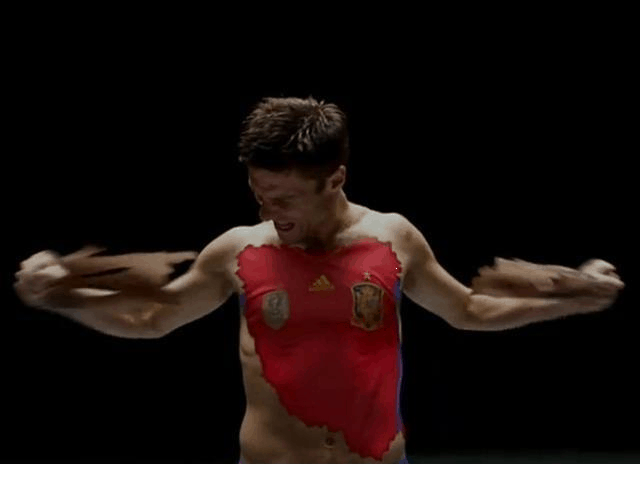

A highlight of Spanish nation building through the 2010 South African soccer World Cup was an Adidas commercial promoting the Spanish selections jersey. The commercial is titled Nace de dentro, “It is born within.” It features two Basque players and an Austrian as they stand with naked upper bodies, handsome, muscular and sweaty. The players (including the Basque player Xabi Alonso, pictured) start stripping their own skin digitally, from under which emerges the national symbol of Spain, and the colors of red and yellow: the Spanish selección’s jersey. Against the backdrop of slow motion soccer field images and dramatic music, a voice over talks: “This jersey is history. It is everything that we suffer for, that we fight for, that we feel and live for. That which unites us is born within.” Rarely is the embodiment of a nation rendered so literal: the athlete’s body is used as a primordial metonymy for a Spain where all are Spanish “under their skin,” in essence, while they may be Basque, Austrian, Catalan etc. on the surface.

In its splendors and miseries, the Spanish selección has been considered a political allegory. Historically, the under-performance of the national team, also known as la Furia Española and La Roja (“the Spanish Fury” or the “Red One”) was attributed to a lack of patriotism on part of players from ethno-regional peripheries (Gómez 2007). Winning the 2008 and 2012 European Championships and the 2010 World Cup, however, bespoke of a different country. The spectacular performance of la Roja was believed to reflect a new unity in diversity: a modern country that has finally overcome its political and social divisions (Delgado 2010).

In its splendors and miseries, the Spanish selección has been considered a political allegory. Historically, the under-performance of the national team, also known as la Furia Española and La Roja (“the Spanish Fury” or the “Red One”) was attributed to a lack of patriotism on part of players from ethno-regional peripheries (Gómez 2007). Winning the 2008 and 2012 European Championships and the 2010 World Cup, however, bespoke of a different country. The spectacular performance of la Roja was believed to reflect a new unity in diversity: a modern country that has finally overcome its political and social divisions (Delgado 2010).

Or has it? For the last two years, various anti-government street fights in Madrid and pro-independence protests in Catalonia and the Basque Country have erupted. As the economic crisis deepens, regional separatist aspirations gain new energies. While the selección’s successes are hailed by Spanish nationalists as uniting the nation, they generate unease at the Basque and Catalan peripheries. Whose desires are really written on the athletes` body? Whose state is embodied? Historically, the peripheries have been instrumental in the development of Spanish soccer and the “Spanish Fury,” while they remain at odds with the idea of a central “Spain.” Soccer and the Spanish selection become what sociologist Michael Messner would call a “contested ideological terrain” in a Spain that struggles to normalize its center-periphery relationships (Messner 1988).

Contested and contesting identities

Sports are a favorite political allegory because, unlike in politics, their agôn or “competitive combat” takes place under more ideal conditions: an “artificially created equality of chances” (Caillois 1961). This premise drives peripheral minorities to compete as subjects through sports against larger, centripetal political environments. Agônic tension between unity and diversity, centre and periphery is palpable between Basque and Catalan soccer cultures and the national selección. The tension has resulted from opposing processes of identity construction: “works of purification” and “works of hybridization” (Latour 1993, Bauman and Briggs 2003). Works of purification disregard alternative affective histories and life worlds, and/or reduce them to a single essence. Works of hybridization allow for the proliferation of diverse identities. These works had as their objective the construction of ethnic, racial and national essences, and fixed ideological rivalries: pro-Spanish centre represented by the Spanish selección vs. Basque and Catalan peripheries represented by regional clubs such as Athletic Club de Bilbao and Barcelona FC.

We see antagonistic processes of purification and hybridization in the history of Spanish soccer. While the Basque and Catalan peripheries, among others, added ideological and ethnic diversity to the overall soccer scene, the “Spanish Fury” served to establish the selección as a meta-discursive regime representing one culture, one language, one territory, one people—Spanish. Symptomatic of the centralist purifying impulse is the very naming of the “Spanish Fury.” Sabino, give me the ball, I’ll wipe them out! This phrase by the Basque player “Belauste” gained transcendence in the history of Spanish soccer. In 1920, the first Spanish selección played an especially physical game against Sweden at the Olympic Games in Amberes, Belgium. Such was the physicality, passion and force of the squad, that they soon were called “Spanish Fury.” In reality, there was little “Spanish” about the event: the squad consisted of 13 Basque, four Catalan, and four Galician players. Belauste himself was a Basque nationalist taking an active role in the Basque Nationalist Party. The Franco dictatorship (1936-1975) affected intensive social, cultural and political homogenization, which purified both the Spanish selección and the entire soccer scene as exclusively “Spanish”; ethnic symbols were banned from stadia all over the country, and clubs had to Castilianize their names. As the oppressive constraints of the Franco regime were removed, we see the re-emergence of regional teams as nationalist symbols. Read more about Capturing context and space in football match analysis.

“Do I feel Spanish?”

The Spanish selección remains a source of tension. On the one hand, there is almost no way the Basque and Catalan peripheries can feel comfortable with it. An impasse of identification emerges because the fan/player subject is uncomfortable with the symbolic persona the selección imposes. “Do I feel Spanish?” “Does this really represent me?” “Why can`t we have our own regional-national team?” When the game is over, Basques and Catalans are declared Spanish world champions, and are celebrated as the finest Spaniards with cries of Viva España! and the chant “Yo soy español, español, español”. But centralist pro-selección fans also feel the vulnerability of their situation: the contingency of the country’s greatest national brand, la Roja, on periphery players that are often openly anti-Spanish. On the eve of the 2010 World Cup final between Spain and the Netherlands, 1.5 million Catalans protested against a constitutional court decision to curtail regional autonomy, and in favour of independence. That particular night before the historic game, the question of what would become of Spain without one of its economic motors, Catalonia, gained another frightful dimension: what would become of the Spanish selección without its Catalan players?

In this political geography we see a process whose logic was analyzed by anthropologist Gregory Bateson as “schismogenesis:” a “process of differentiation in the norms of individual behavior resulting from the cumulative interaction between individuals” (Bateson 1958). As each party reacts to the reaction of the other in the process of progressive differentiation, and unless there are restraining factors, the end result will be a schism. Historically, the equilibrium of both the political system between centre vs. periphery, as well as the sports system of Madrid vs. Barcelona and Bilbao, have been restrained by state domination and purifying discourses. The system did not disintegrate because there was a situation of “complementary schismogenesis:” a competitive relationship between categorical unequal, between centre and periphery. The current possibility of disintegration lies in a shift from complementary towards “symmetrical schismogenesis:” a shift towards a competitive relationship between categorical equals which, in the absence of restraining factors, may lead to a breakaway situation. Indeed, we see an unprecedented constellation of circumstances: 1) in a supra-national democratic Europe, centralist constraints on regional self-determination are increasingly untenable; 2) Catalan players define a new play style and dominate the Spanish selección more markedly than ever; and 3) Spanish soccer receives more media scrutiny than ever. These factors create increasing symmetry: the growing symbolic capital of Catalan soccer turns the periphery into a categorical equal.

Football Perspectives about Catalans who are making no secret of how they wish to use that capital: at the 2012 October el Clásico, the derby between Real Madrid and Barcelona FC broadcast by 680 journalists from 30 countries and viewed by 400 million television spectators, the Camp Nou terraces displayed this message on a giant board: “Catalonia, Europe’s Next State.” As the “Madrid-Barça” is increasingly conceptualized as “Spain-Catalonia,” it becomes an event that stimulates latent potential for disintegration in politics and in sports, as the rivalry is feared to negatively affect the Spanish selección. In the face of Spain’s divisions, the “Spanish Fury” has been actively constructed to inhibit disintegration. However, with recent pro-independence proclamations, the Catalan dominance of the selection, and the politicized spectacle of the Barcelona-Real Madrid rivalry, the question arises: will soccer and la Roja inhibit the nation’s schismogenic tendencies, or will they further fuel them?